Writing

Project Details

Title: The art of trash

Category: Writing

Date: 23 November 2015

Share:

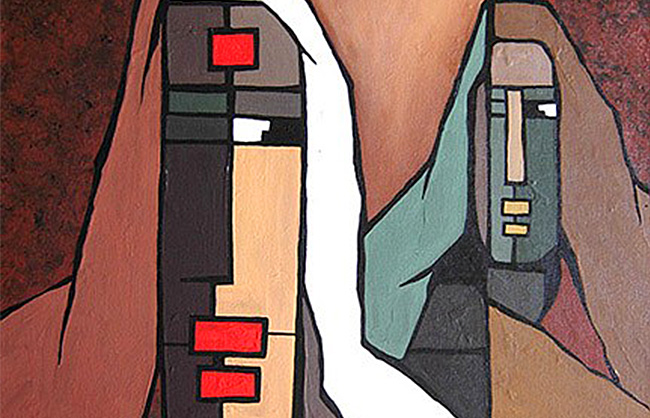

While gallery spaces in Kathmandu have appeared more or less inclined towards rather conventional exhibitions of paintings on rectangular canvasses, an exhibit of sculptures has come to stake its territory, one that is unlike anything we’ve seen so far. Lyrics from the Junkyard, a show by artist Meena Kayastha, that began on 19th August, has brought with it fresh perspectives yet unseen by Nepali viewers. Kayastha’s works are amalgams of primitive art-forms and contemporary sculptures, where objects from the junkyard are brought to life—doused in native earth-tones and given imaginative shapes and figures.

Kayastha describes always being strangely drawn towards the various discarded objects that one comes across everyday, and seeing in them a unique aesthetic charm. Though the concept of a show based on junk had already begun forming in her mind, it wasn’t until two years back that she actually started working on her pieces. Besides, this was a completely new approach for Kayastha, who, prior to this, in the numerous group exhibitions that she’d participated in over the years, had focused mainly on works of cement, with hints of cubism within. This time, however, she seeks to find forms within those objects that lie forgotten in the junkyard—things that would otherwise be considered useless and unwanted—converting them into art and giving them a renewed role and purpose.

“Junk has a particular feeling for me. A feeling of being discarded, undesired, overused and aged with passing time,” Meena explains. “Junk is junk, I can’t really compare it to anything else that has a momentary value. Any given piece of junk once had a life, had importance and meant something to someone who owned it. People got things done with it. Over the years, the sun beamed on it, rain drizzled on it, friction rubbed off its surface, air layered rust all over it and usage lessened its purpose. There, it

transformed into junk. Useless. I fear that is the fate of all of us.”

When the artist finally began work on the series in 2009, it was very labour-intensive; she found herself frequenting the junkyards in and around Kathmandu and hauling pieces back home. She would look over the piles of trash to select items that appealed to her. And then she would start experimenting on these. Numerous pieces would sometimes need to be fused together to make a single piece. “I never planned on what I wanted to make beforehand; that would’ve made the work dull and devoid of artistic passion. I’d only discover it myself as the pieces progressed and shapes appeared,” Kayastha shares.

As one moves through her works, one can see a variety of structures ranging from those that are 2 ft tall to some that are a looming 6 ft. The 25 pieces built intricately around junkyard offerings reflect Kayastha’s progressive style. Her thoughtful primal pieces are very distinctive, and each has a story of its own to tell, built as they are around positive human emotions “Navarasa”, which includes motherhood, ageing, love among others. The works are hybrids of post-modern mechanical structures infused with primitive figurative art, which have been molded with papier-mâché, mud, welding and in some cases, wax. These figures look almost tribal—Kayastha has toned her pieces with traditional hues of Tera Singelata, mud brown, whites and smoke black—contrasted brilliantly against the sharp modern-ness of the mechanical frameworks.

The structures are also highly reminiscent of various global art strains—African art, for example, and of the exaggerated figures characteristic of the works of Brancusi and Marcel Duchamp—boldly enunciating the Dada reflections within her style and vision. The black lines that run over a few figures, creating intricate patterns, are strikingly similar to those that comprised the essential design element in primitive Pueblo art from Santa Carla, Mexico—not only adding to the visual harmony, but in tracing the shadows formed when the sculpture is lighted up, incorporating a whimsical, surrealist feel. There is also touch of sadness about Kayastha’s figures, a feeling of collective loss; the prominent use of metallic parts and mirrors from old bikes, for instance, appears to symbolise how delusional we’ve become in our everyday lives, forgetting the fragile transience of our own existence. Similar emotions are conveyed through the intentionally disoriented and disproportionate shapes given to the pieces.

The skill with which the artist moulds her emotions into her self-portrait is reflective of her dual realities—she is both a worldly and a free soul. Amidst the misshapen figures, there are some pieces that use human teeth and the artist’s jewellery, adding vibrancy as well as a human element to the display. These old geezer faces in subdued earthly tones, with mouths open, hands suggestively pointing in all directions and patterned in smoke black to portray the shadows, all promise to change the way we see junk.

“I fear ageing. I fear losing my enthusiasm, energy, lust and youth. Nature says it can’t let me live forever, but I could

still immortalise my feelings and my thoughts. Junk has feeling, and I feel I am meant to bring it out so that the world can see it, feel it,” says Kayastha.

Lyrics from the Junkyard will be on display at the Siddhartha Art Gallery at Babarmahal Revisited till September 9.

Printed on: AUG 19