A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_URI::$config is deprecated

Filename: core/URI.php

Line Number: 101

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Router::$uri is deprecated

Filename: core/Router.php

Line Number: 127

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$benchmark is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$hooks is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$config is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$log is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$utf8 is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$uri is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$exceptions is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$router is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$output is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$security is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$input is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$lang is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 75

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$load is deprecated

Filename: core/Controller.php

Line Number: 78

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$db is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 390

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_DB_mysqli_driver::$failover is deprecated

Filename: database/DB_driver.php

Line Number: 371

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::open($save_path, $name) should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::open(string $path, string $name): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 132

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::close() should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::close(): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 290

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::read($session_id) should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::read(string $id): string|false, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 164

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::write($session_id, $session_data) should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::write(string $id, string $data): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 233

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::destroy($session_id) should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::destroy(string $id): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 313

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Return type of CI_Session_files_driver::gc($maxlifetime) should either be compatible with SessionHandlerInterface::gc(int $max_lifetime): int|false, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice

Filename: drivers/Session_files_driver.php

Line Number: 354

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 284

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: session_set_cookie_params(): Session cookie parameters cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 291

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 306

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 316

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 317

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 318

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 319

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: ini_set(): Session ini settings cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 377

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: session_set_save_handler(): Session save handler cannot be changed after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 110

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: session_start(): Session cannot be started after headers have already been sent

Filename: Session/Session.php

Line Number: 143

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$session is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 1279

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$form_validation is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 1279

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$email is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 1279

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$help_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 353

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$front_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 353

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$data is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$benchmark is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$hooks is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$config is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$log is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$utf8 is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$uri is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$exceptions is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$router is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$output is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$security is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$input is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$lang is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$load is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$db is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$session is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$form_validation is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$email is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$help_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$front_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/core/MY_Controller.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property Home::$other_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 353

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: 8192

Message: Creation of dynamic property CI_Loader::$other_model is deprecated

Filename: core/Loader.php

Line Number: 925

Backtrace:

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/sworup/controllers/Home.php

File: /home/sworup/public_html/index.php

A skipped beat

Project Details

Title:

A skipped beat

Category:

Writing

Date:

17 November 2015

Share:

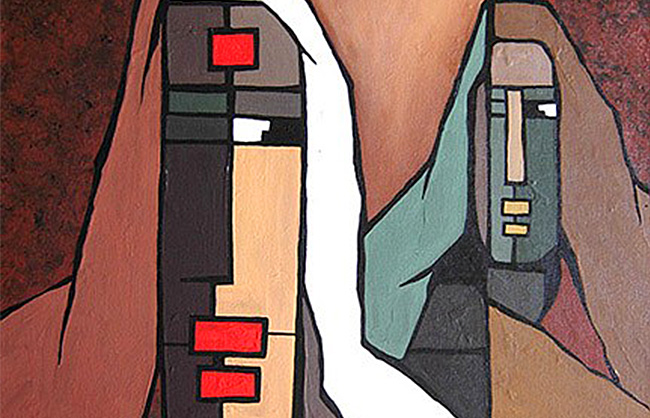

Anyone who remembers Birendra Pratap Singh’s last exhibition features the dwindling landscapes of Bhaktapur in pen and ink, will be looking at his current display at the Kathmandu Contemporary Art Centre with widened eyes and an open mouth. Not a single piece of this series has been sold, and this, for an artist, whose work never returned home after being put on display. The artist sought a major shift in form and subject to the predominant theme in most of his work over the past 16 years — the environment.

Of course, there is a reason. Adhering to his minimalist lines and intricate detailing, this master’s current muse in mixed media, his exhibition entitled Electrocardiogram Internal Stories, portrays the realms of the boredom, clumsiness, and complicacy, all set in contrast to the angst of a patient in hospital. The process and phases of hospitalisation, and its stressful impact on the patient and all those who attend him, is a theme explicitly explored in the various works that comprise Singh’s collection. The series is thus not just art, but a public perspective of the tedious ramifications between the health institute and its patients.

The artist, a former illustrator of the Gorakhapatra Sansthan, was inspired by his own experiences with the troubling theme. Singh was forced to face a hospital environment for several months when his brother had a heart attack two and half yeas ago.

“We were at the Apollo Hospital in New Delhi,” Singh recounts, “My hands were on my brother’s chest. He had had a stroke, and before he was treated, the hospital conducted a number of examinations, including the Electrocardiogram (ECG). When the report came, we learnt that he had to be operated on, but we waited for six days before he entered the operation theatre. I remember seeing patients’ relatives waiting for answers in cold, air-conditioned rooms or outside, getting bitten by a hoard of mosquitoes. It was possibly hospital policy to keep them away from the patients, but the sense of suffering in those spaces was something I just couldn’t ignore or forget. “

With great clarity, the exhibition puts forth the message that while the patients may be treated over time, the trauma for those waiting for their recovery is, almost ironically, far more long-lasting and difficult to heal. This suggests that health institutions as a whole need to look into how they are healing and not just treating people they take into their care.

Never had anyone thought that this artist, with his history of drawing Banaras, Bungmati, and Bhaktapur images, would be the one to create such drastic work in the contemporary South Asia. Apart from the lyrically minimalist approach, the stage that the exhibition sets up is completely different from current trends. “Birendra spent many years portraying an endangered environment and heritage monuments in his drawings”, Sangeeta Thapa, Director of Kathmandu Contemporary Art Centre comments “This preoccupation seems to have come to a close as the artist focuses on a new area of concern-the ailing human body.”

The artist fearlessly takes on the difficulties of blending an abstract style with visceral public concerns. With intricate details as those often seen in the works of Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt, he intensifies the existing problem by stressing on state of the fraught individual caught within the shock of having to deal with disease, and the indifference of the external environment.

As one enters the exhibition hall; one encounters 59 relatively small and medium sized pieces of art which seem rather similar at a first glance. It is only with a closer look and keen eye that the details pop up, especially in the case of smaller paintings that have been put together in groups.

Perhaps a result of all his experience in printmaking, the compositions in each of the pieces is extraordinary. His canvasses leave ample white space, and while in other works, this might make the piece look unfinished, here, the presence of the space makes the painting complete. Black patches, suggestive of human figures, are strewn across, as though standing in hospital queues. Audacious strokes of black and finger splodges on ivory paper over a layer of glue stick — later on washed off — depict medical X-Ray prints, intricately displaying the machine-like internal organs of the human body.

A viewer cannot but wonder about the X & Y dimensions that depict a central element of these works; the ECG. The bright yellow and orange rectangles that balance the painting are actual cut-outs of the artist’s own ECG report, and he has not failed to add to the visual appeal, by placing pieces of aluminium foil that form the deceptively shiny LCDs of the ECG device.

Singh’s works incorporate rich, metallic colours like copper, silver, and Japanese black ink, with each symbolising the red blood cells, the white blood cells and the diseased body parts respectively. Mystical birds hover over these figures, questioning the overall theme. These birds, as the artist clarifies, are symbolic representation of the experienced eyes that read the complicated graphical ECGs.

The paintings keep the viewer guessing and thinking. The medium-sized canvasses in particular, portray emotive Egyptian-like pregnant women also waiting in queues to see a doctor. Only with a detailed study, do small figures of hearts and an occasional computer mouse stand out from the midst of the bright tones. A few of these figures — detailed images of nude women with a seemingly boneless flexibility — hint of the artist’s sarcasm and the poignant reality that lies beneath. “I felt like a physician, a surgeon, and a diseased patient, all at once, while I worked on these,” says the artist.

Singh denies that his works are destructive forms – “You have to be influenced by external elements — films maybe, or literature — to visually distort a human body. My figures have heads, bodies, proportions — they are delineations of realism”.

Undeniably, Birendra Pratap Singh has found artistic value in unexpected places and in objects created for other-than-aesthetic reasons, and has honestly realised his commitment to social reality. But whether art enthusiasts in Kathmandu will be able to understand and appreciate this sophisticated display of conceptual abstract art remains a question to be answered.

(Electrocardiogram Internal Stories was showcased at the Kathmandu Contemporary Art Centre at Jhamsikhel, Lalitpur till 16th February. The artist, now living in Dhulikhel, has hinted that his next series of paintings will be based on dissimilar facets of the Buddha.)